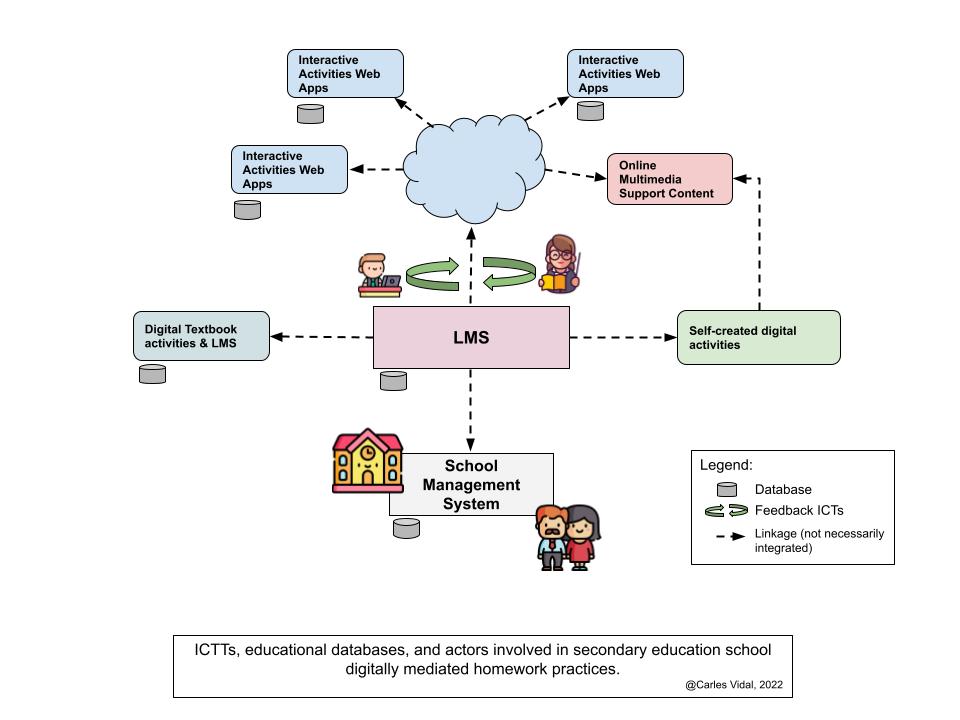

Keeping the focus on secondary schools’ Virtual Learning Ecosystems (VLEs), this new contribution to the blog presents a model of a VLE, based on a series of recent interviews with maths teachers mentioned in the previous post. The model is an abstract representation of the types of information and communication technologies for teaching (ICTTs) currently at play during digitally mediated homework practices, as well as of the key actors intervening throughout this learning strategy, including teachers, students, the school and parents.

As the image suggests, VLEs are organized around a central block, the learning management system (LMS), a software infrastructure whose purpose is to support virtually any educational demand throughout the learning process. The length and scope of each LMS may depend on its actual school implementation, however, all of them allow structuring courses and content, provide access to third-party resources and support a variety of roles (teachers, student administrators, collaborators… ) favouring their interaction and the monitoring and storage of all educational data. Furthermore, given their fundamental position within the model, LMSs are intended to collect data from other (peripheral) ICTTs with which they may be integrated, such as digital textbooks, online content applications, content creation tools, online multimedia repositories and school management systems (SMS).

When it comes to managing digital assignments, teachers and students are bound to visit a variety of virtual settings. Therefore, a typical homework sequence may involve assigning tasks through an LMS (such as Moodle, Google Classroom or Teams), then, navigating to the linked resources hosted in another application, and, carrying out the requested tasks (which may as well lead students to further online resources). Once the task is completed, follow-up and assessment practices may take place through different blended learning strategies, depending on the type of assignment and the teacher’s didactic views. In this sense, some tasks will be discussed in-person during classroom time and assessment will be provided on paper, while other exercises’ completion will only be checked and corrected through the corresponding ICTT. To complete the picture, all along the homework process, student-teacher feed-back can be provided through a variety of ways (email, posted comment, chat message) and media (written, sound bit, video clip), on any of these ICTTs.

This lack of centralisation causes workflow inefficiencies in the homework process, can lead to students’ attention loss and requires teachers to act as the true interoperability tool for learning (driving them to check homework completion and assess assignments in different applications and to manually upload data from one environment to another, among other actions).

Moreover, as tasks are performed in different environments (e.g. an algebra exercise may take place in GeoGebra, while a fractions’ activity may require the use of Jamboard) the results and educational data are stored in their corresponding and dispersed databases. In principle, all these ICTTs can interoperate with each other, recognising their users and exchanging data through interoperability protocols (which allows us to describe these complex assemblies as ecosystems made up of different environments). However, in most cases, integration is not fully achieved, for various reasons that could be described in another post. This lack of centralisation causes workflow inefficiencies in the homework process, can lead to students’ attention loss and requires teachers to act as the true interoperability tool for learning (driving them to check homework completion and assess assignments in different applications and to manually upload data from one environment to another, among other actions).

How do we make VLEs work better? One way to analyse the problem is by paying attention to who is making the decision to use which technology and what are the incentives and motivations at stake. While the exact answer depends on each school, in general, school administrators (after some dialogue with teachers and families) decide over LMSs, digital textbooks (when used) as well as on the SMS, as these are structural elements that require a unified school strategy. On the other hand, teachers are constantly exploring and trying new content applications or support tools that will help them cover the curriculum, improve practice and provide feedback and assessment. In this sense, teachers are best placed to identify and assess subject-specific ICTTs that bring real educational value to their classes.

As a result, some technologies come from of a top-down decision process, while others are adopted through of a bottom-up one. The first group is planned out from a school strategy perspective, while the second one is dependent on each teachers’ didactic approach and tech knowledge. Therefore, it seems clear (and it is precisely the point of this post) that an informed dialogue between all affected stakeholders is needed to ensure that the different components of these complex ecosystems are well integrated, balancing strategic school needs and educational ones at class level.

Featured image rights: “Infinity Mirrored Room—My Heart Is Dancing into the Universe” by Yayoi Kusama. @Hirshhorn.